– The World We Never Know –

No one can be exempted from the need for sleep. In sleep, we are restored and refreshed while suspending between bodily functions and consciousness. We do not know what was happening when lying asleep. Further, those almost in a trance are cut off from reality. What is the relationship between the actual world and the realm reigned by Hypnos?

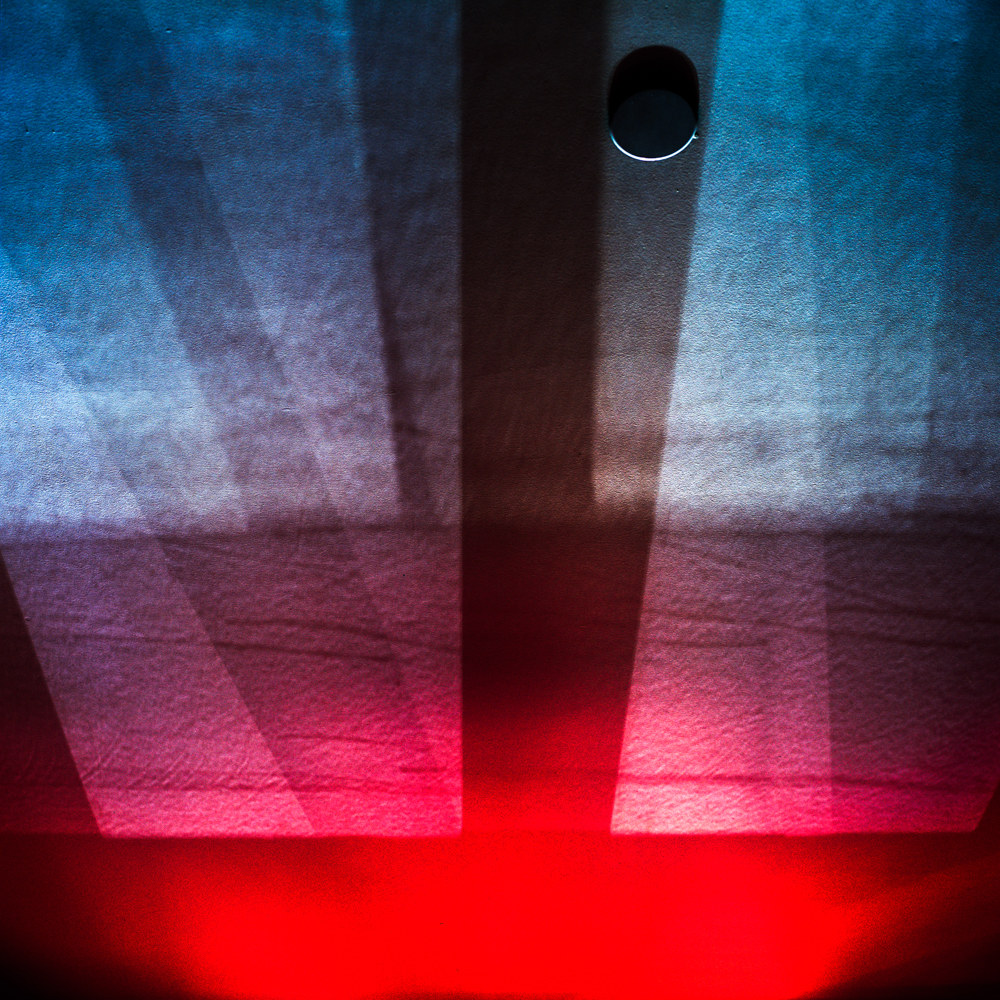

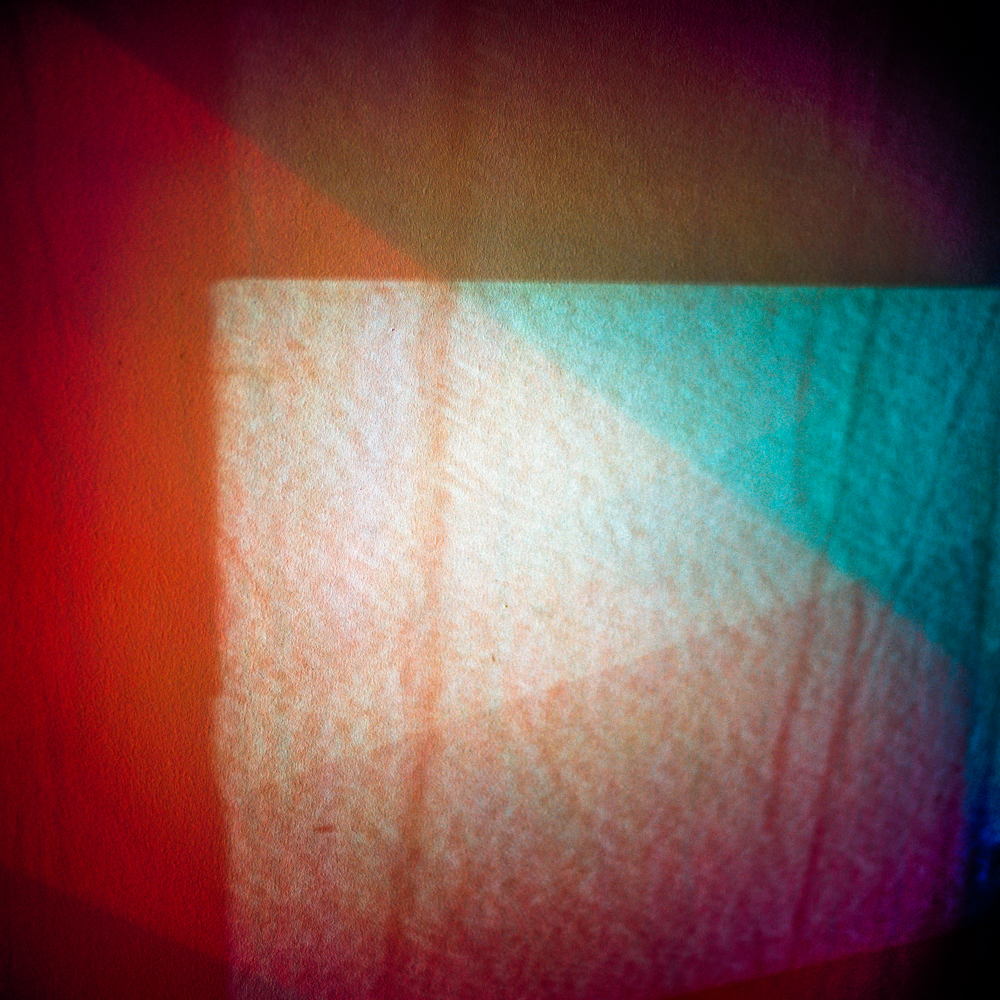

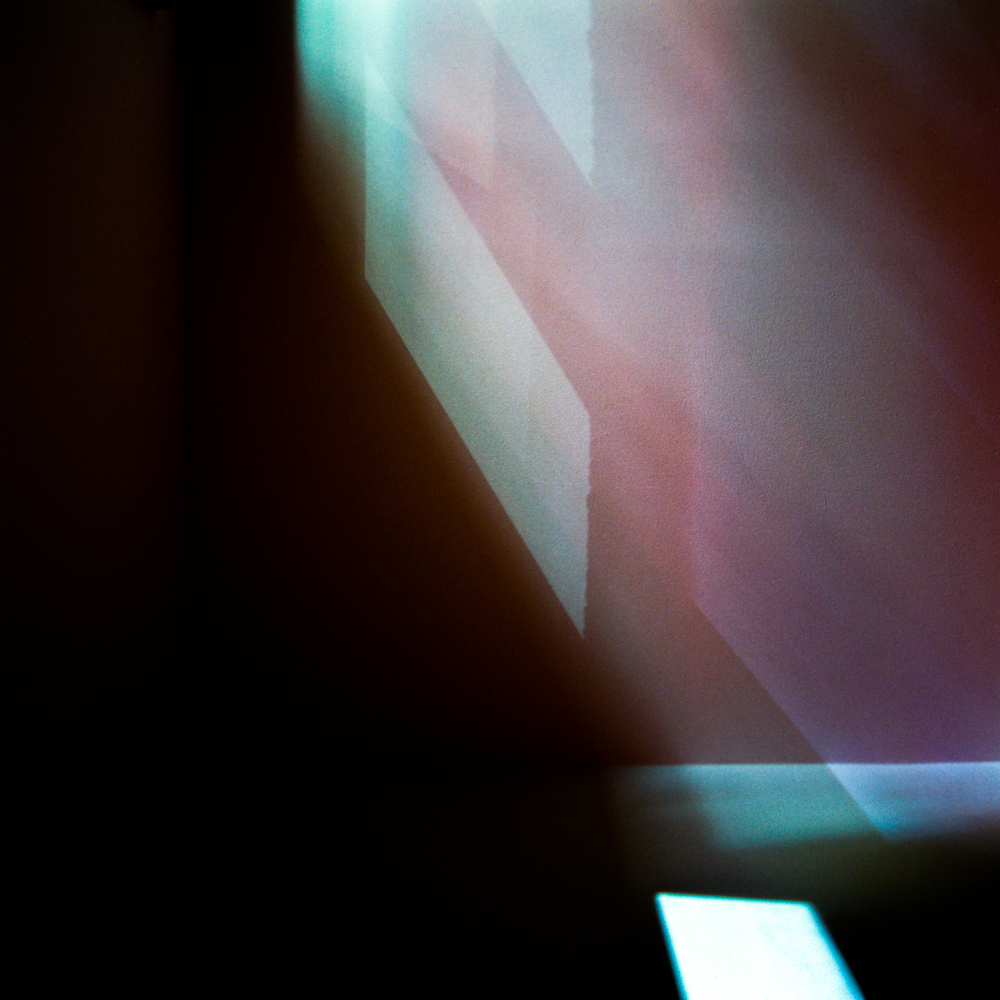

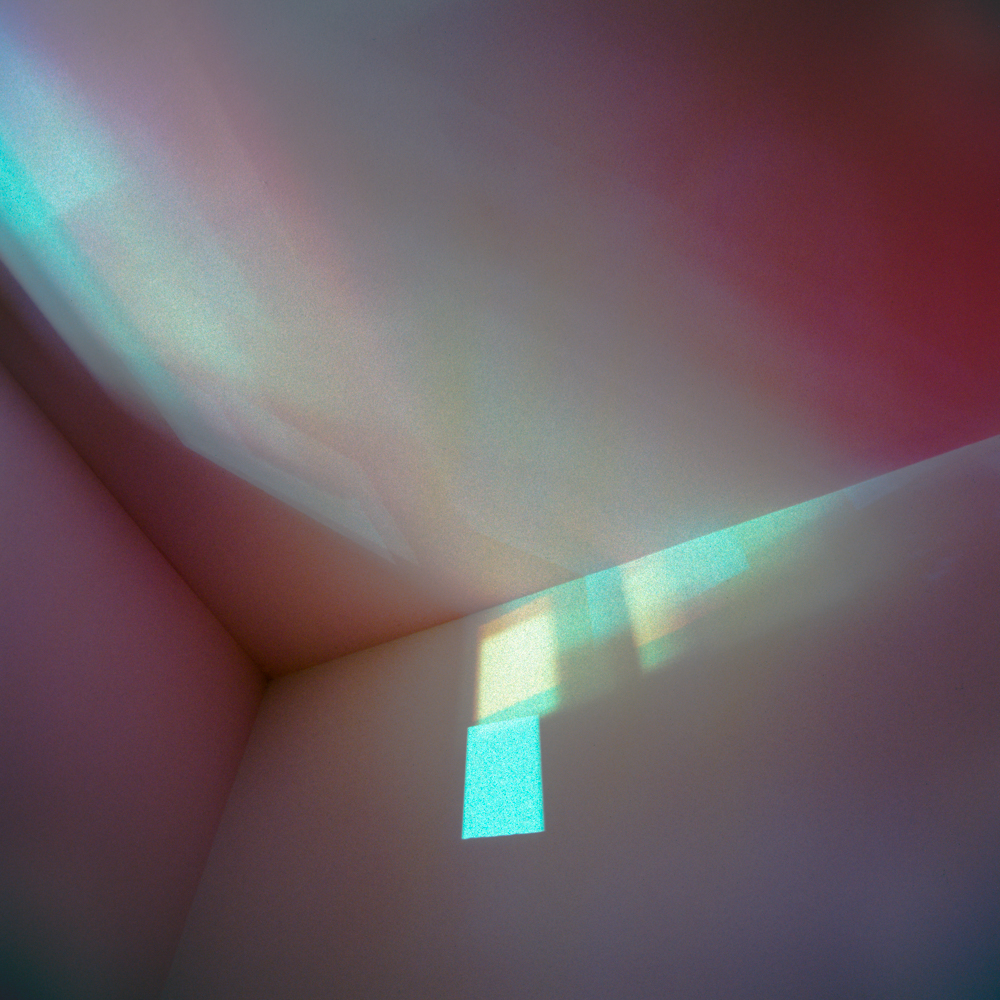

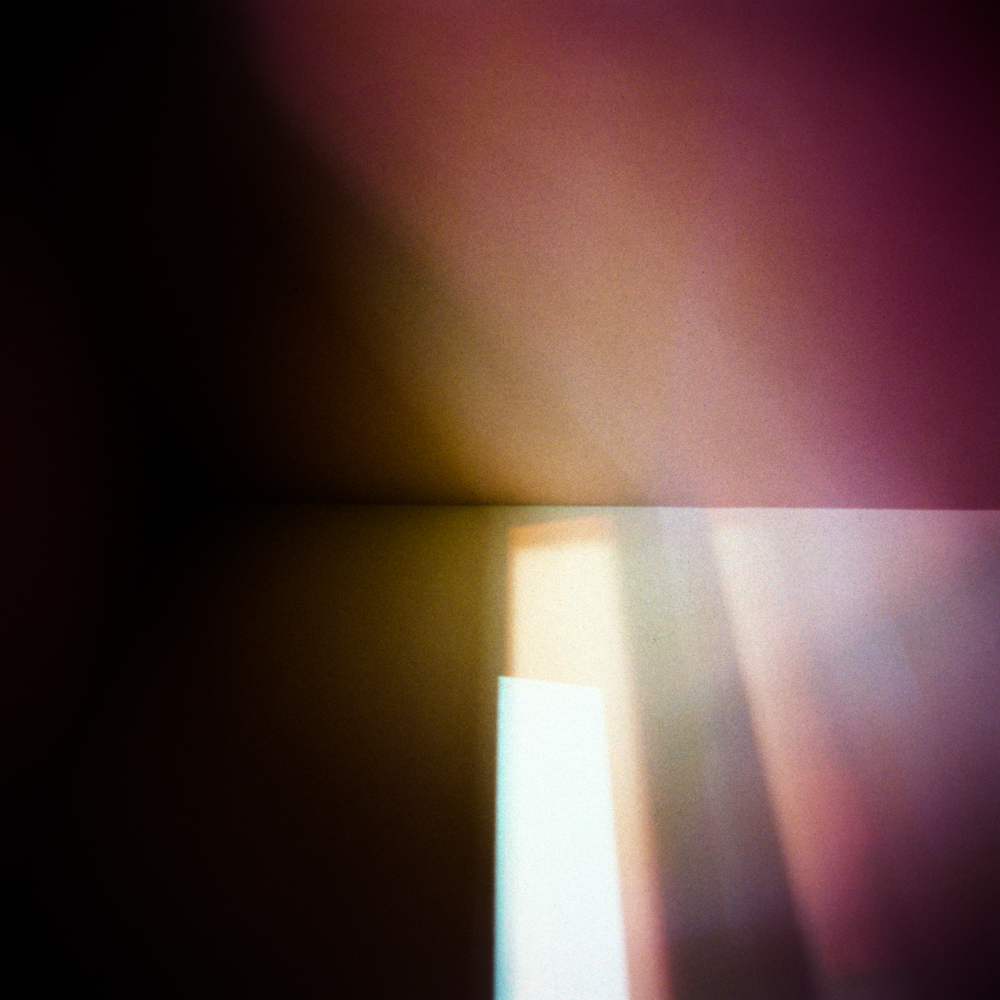

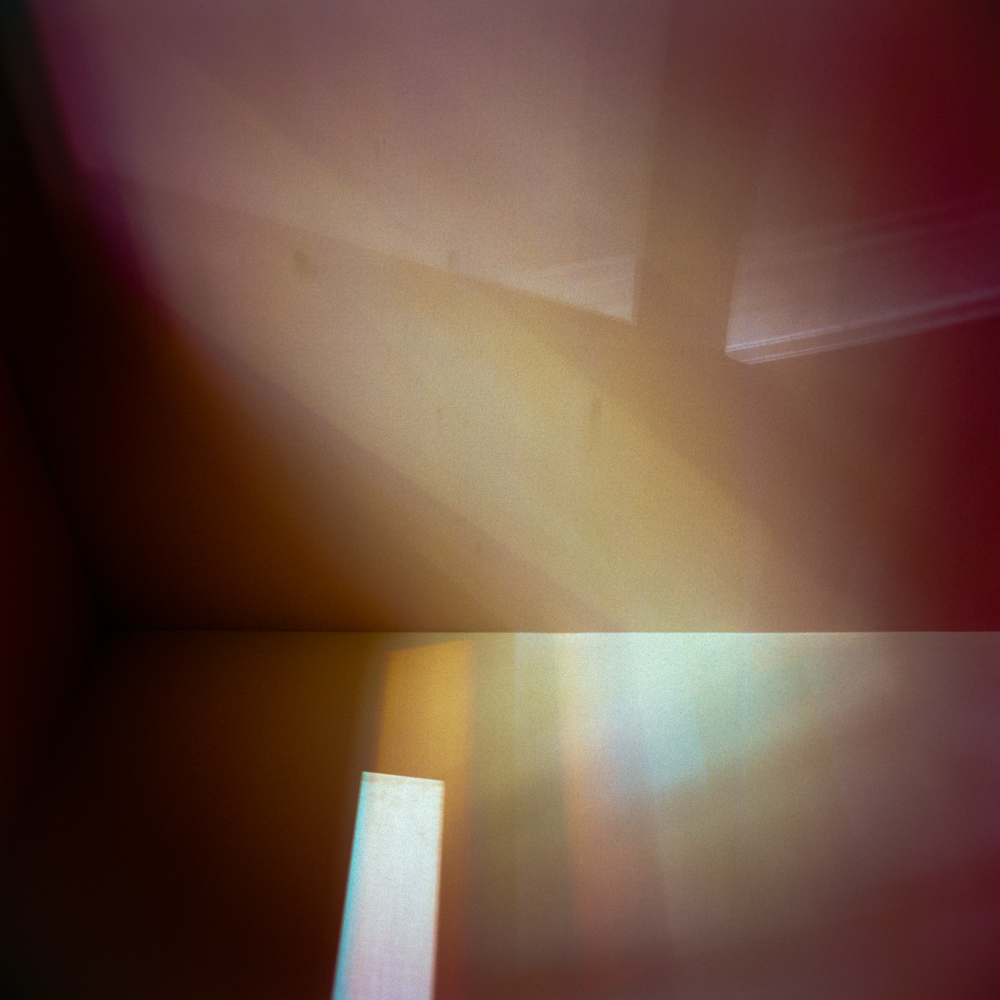

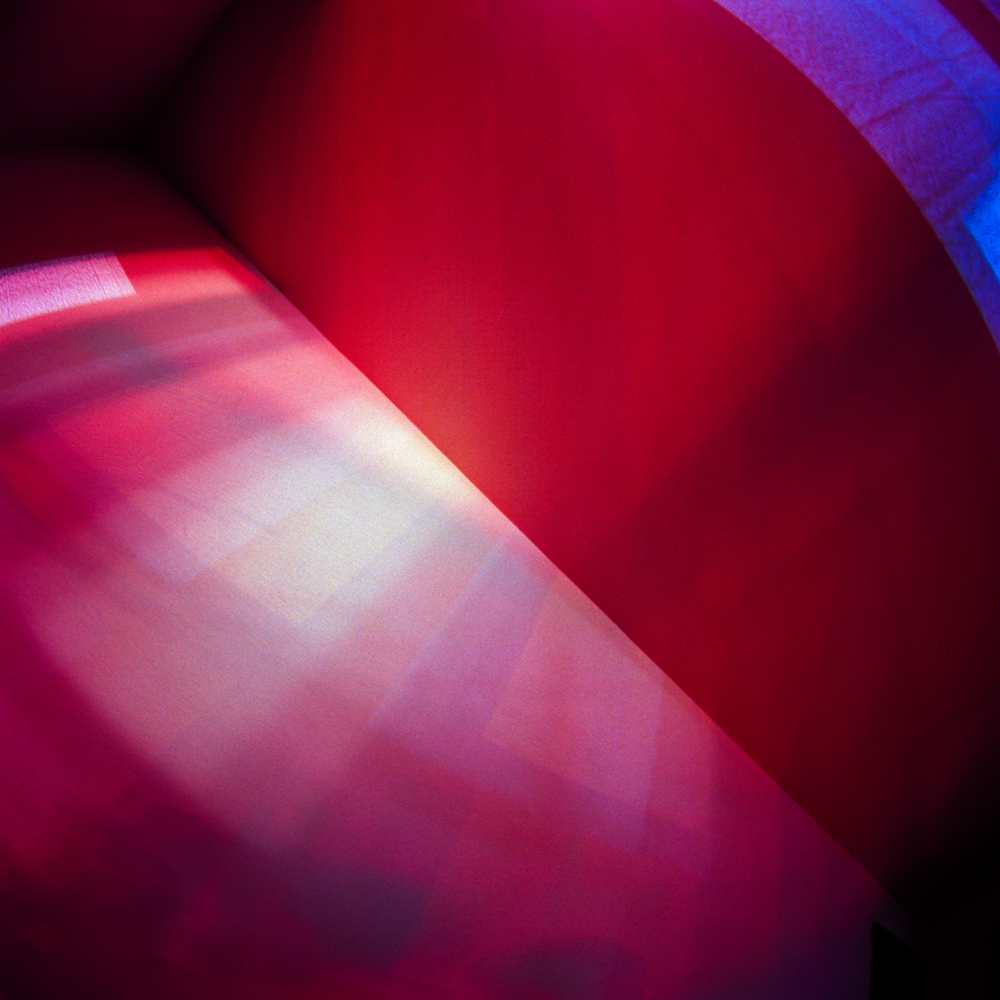

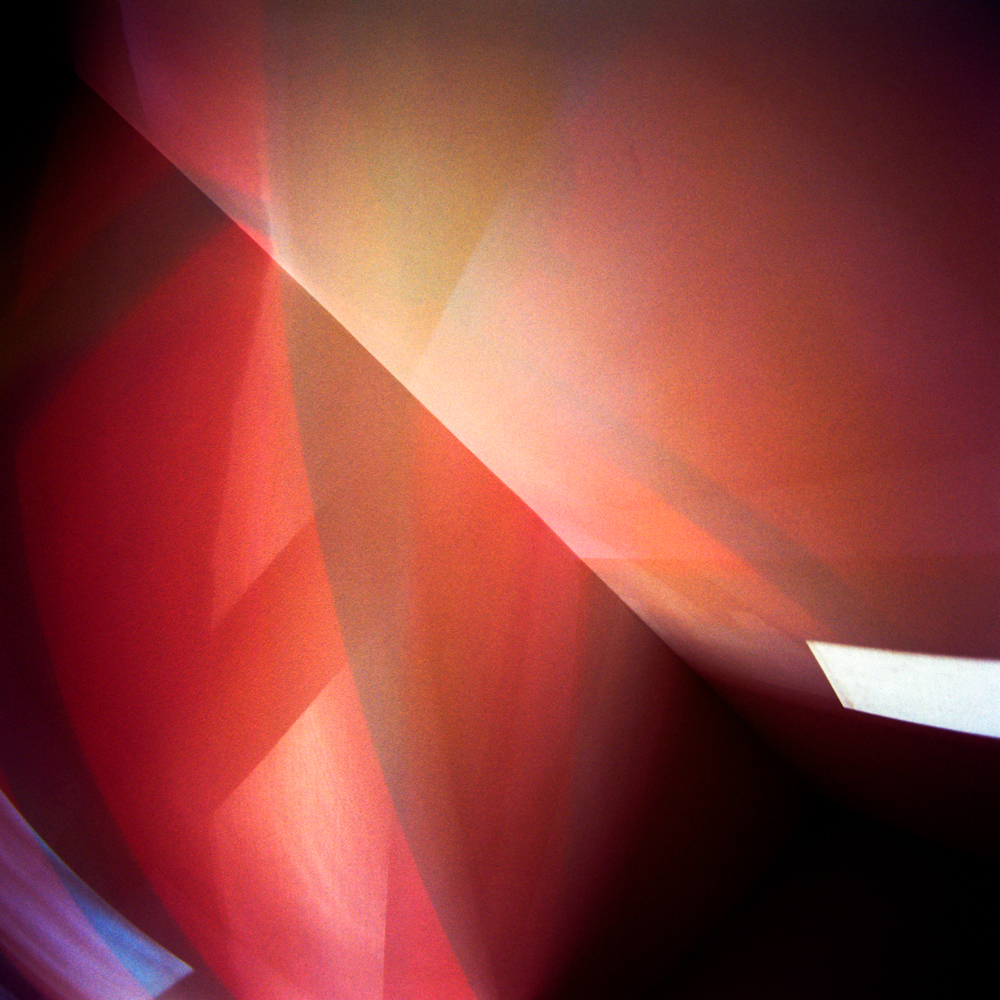

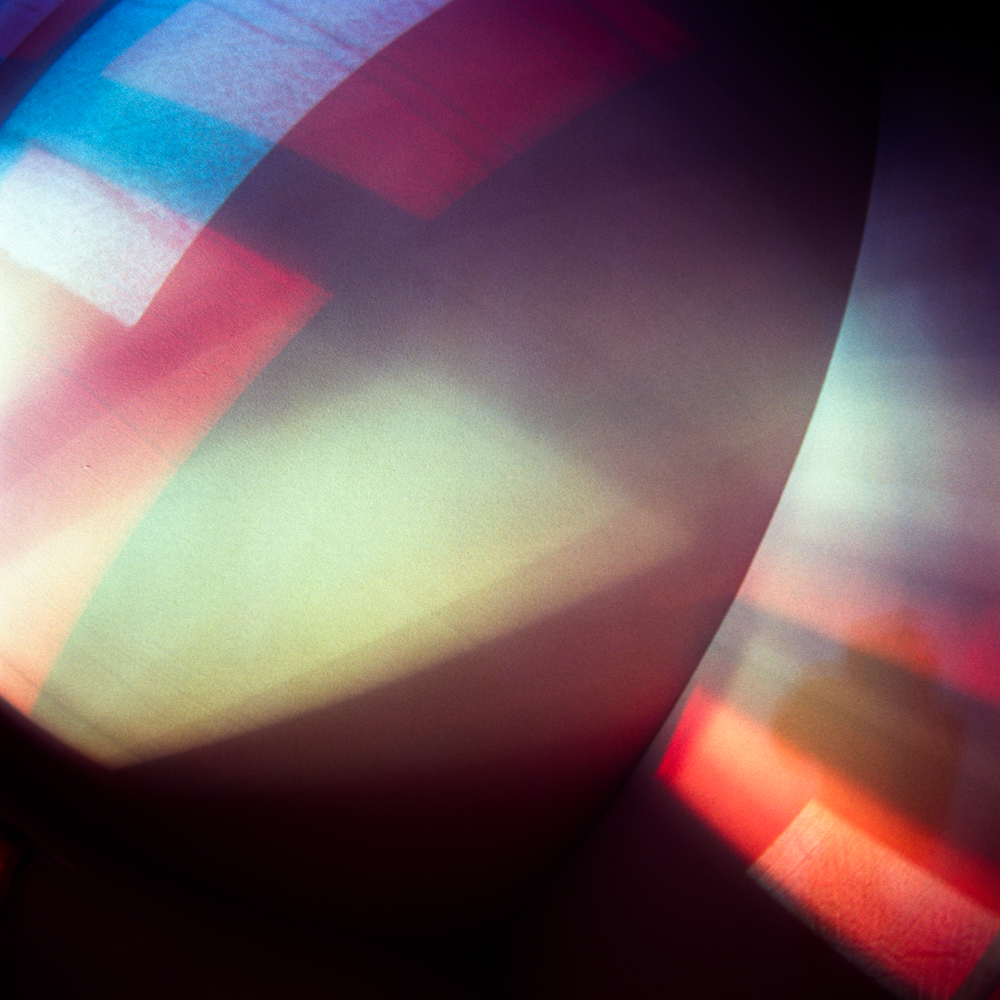

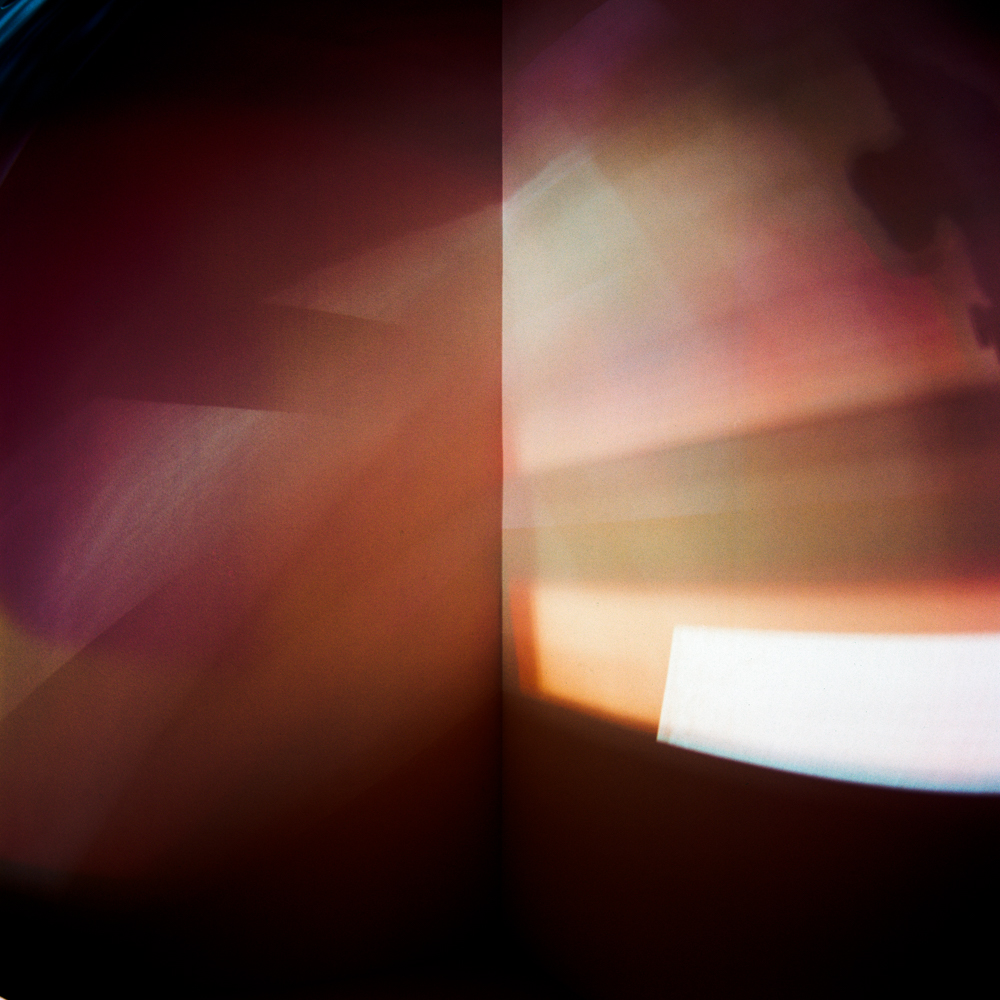

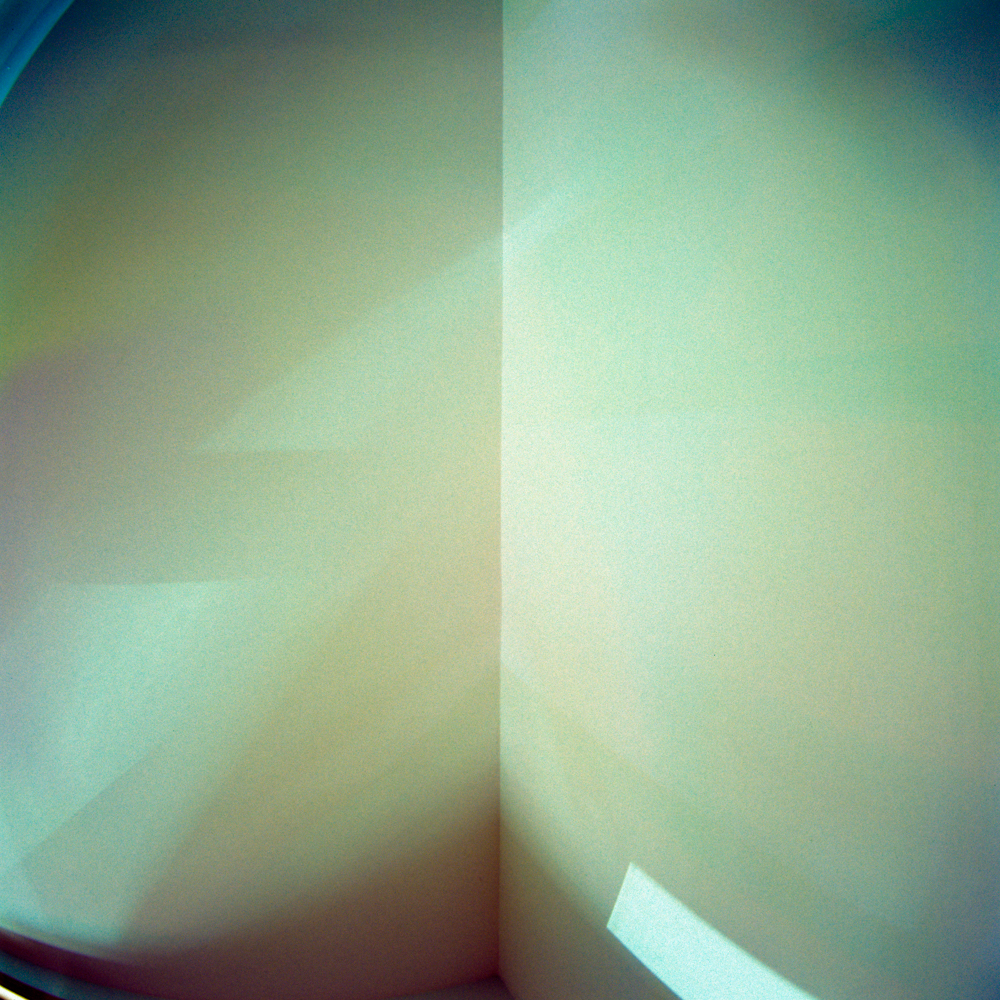

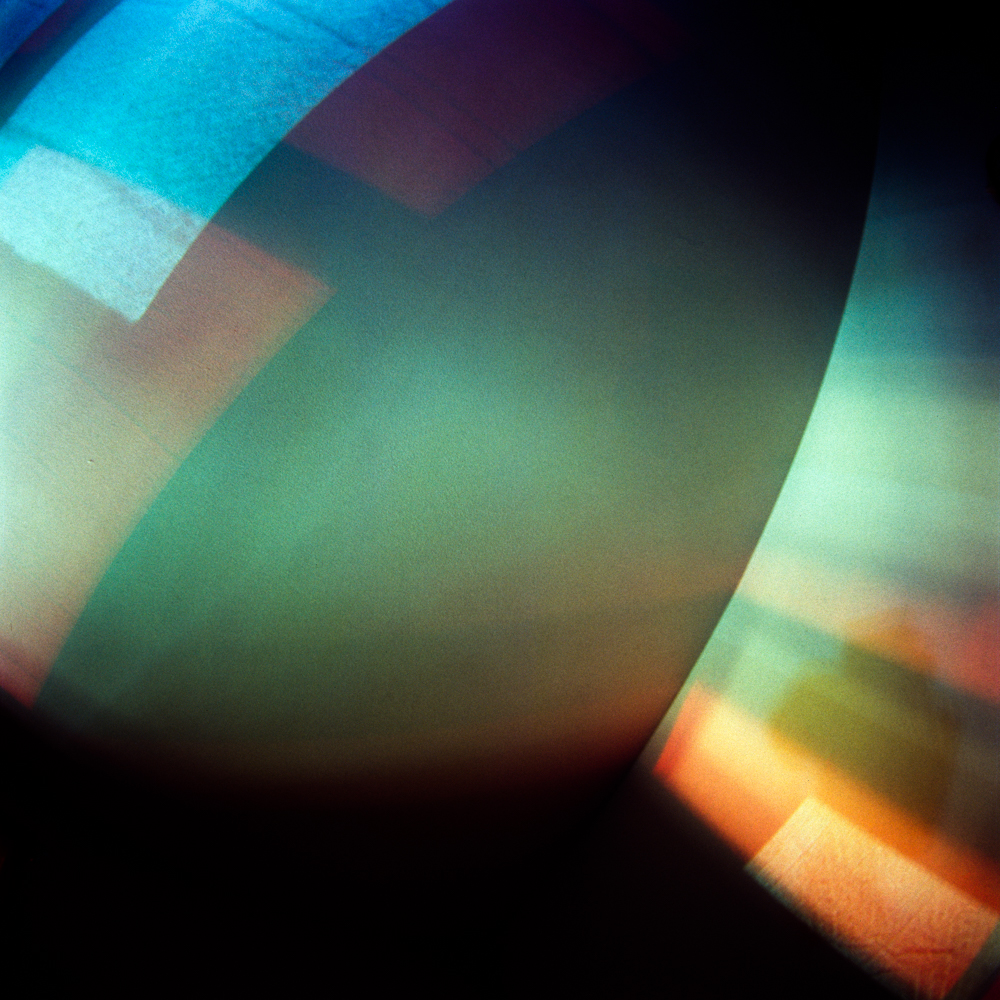

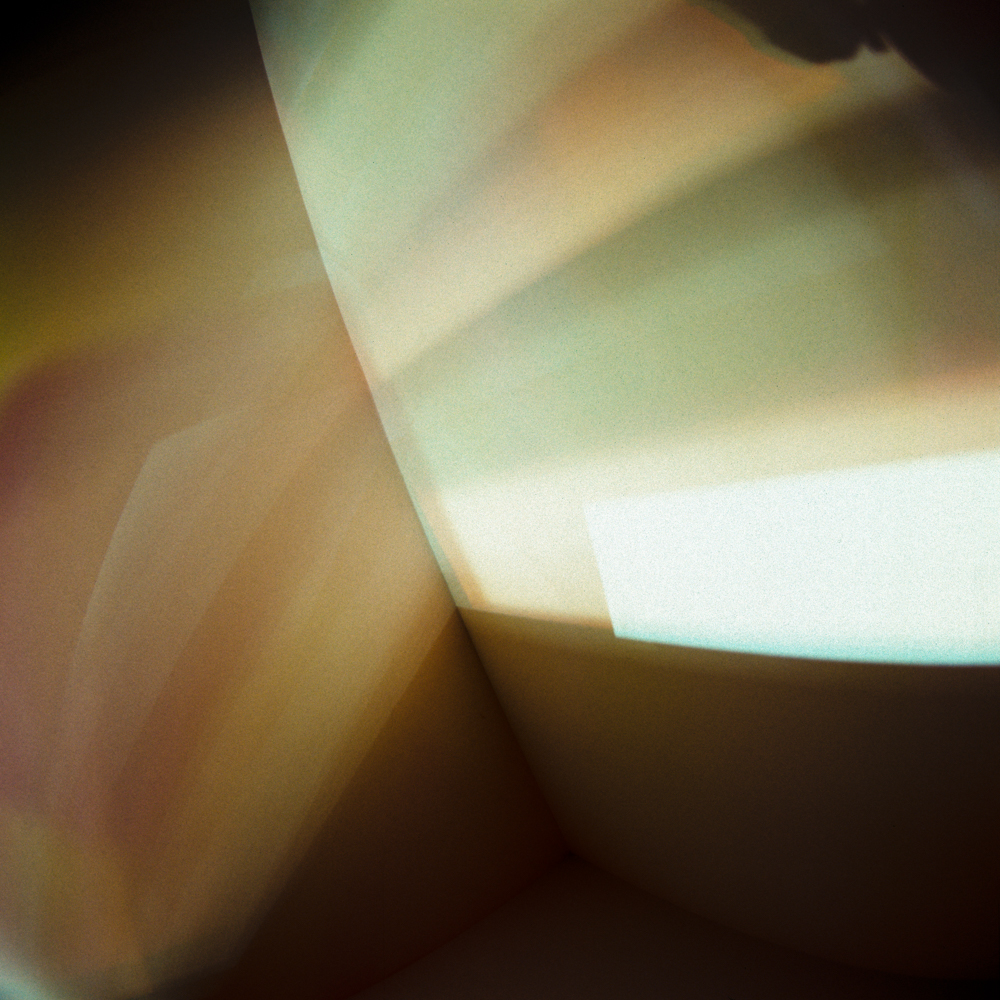

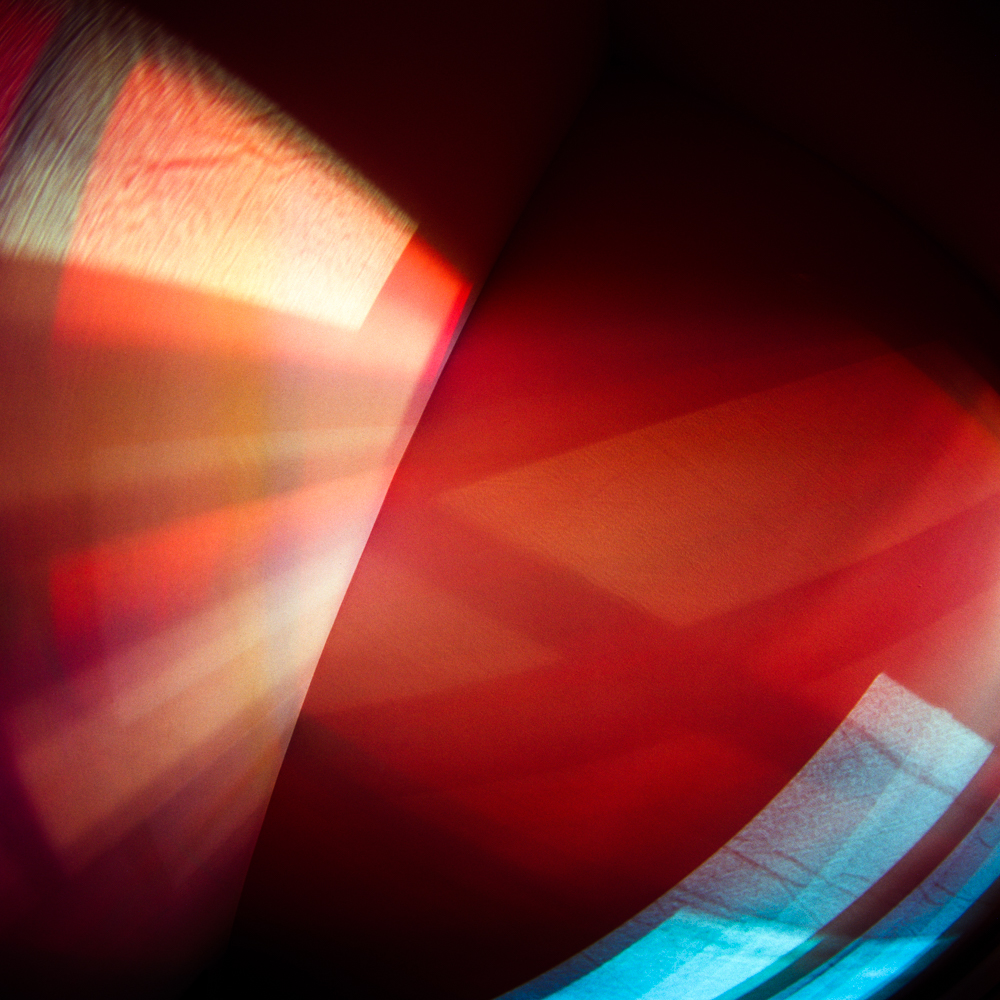

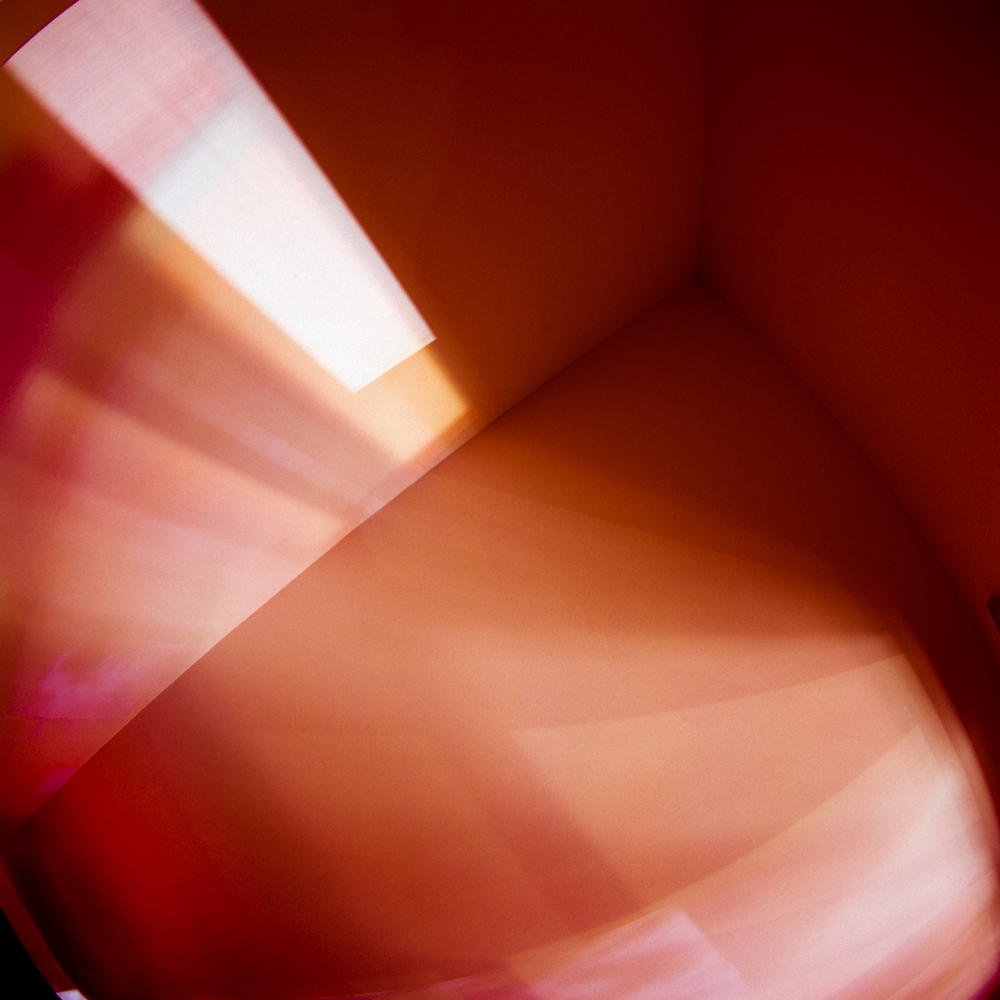

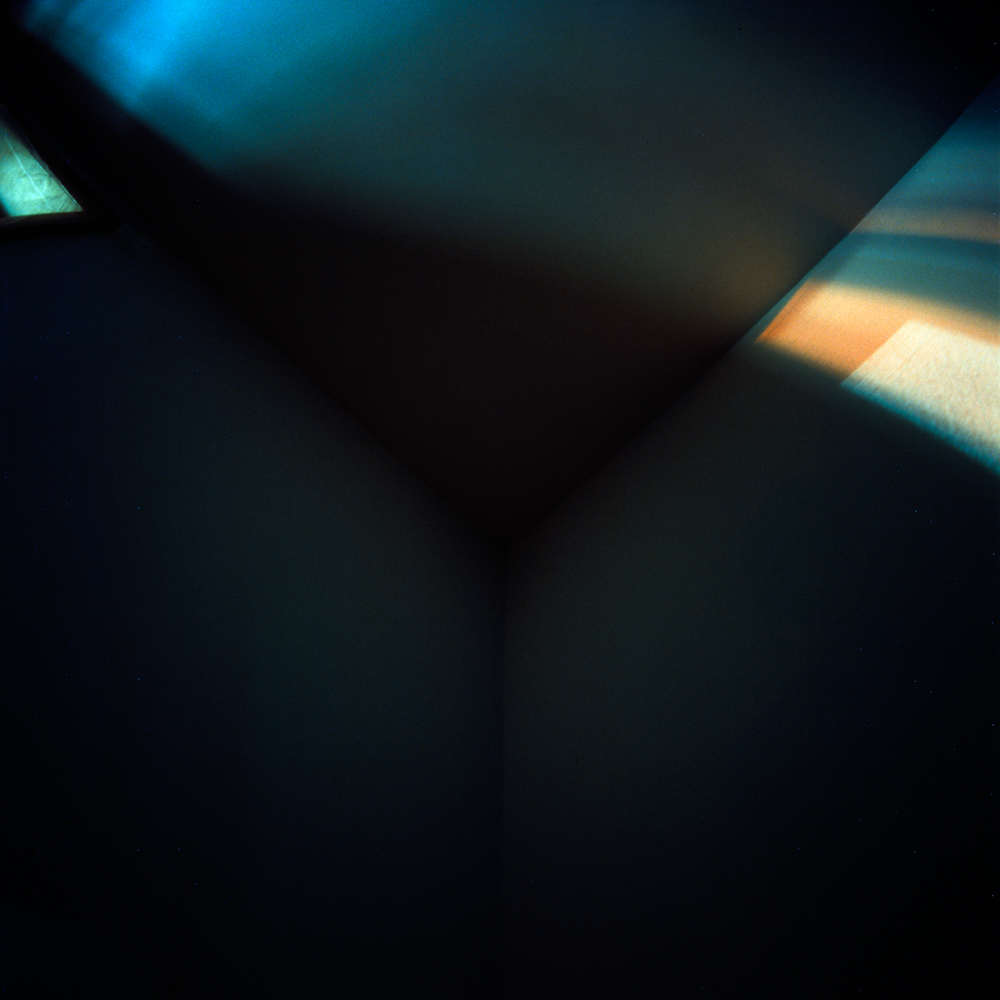

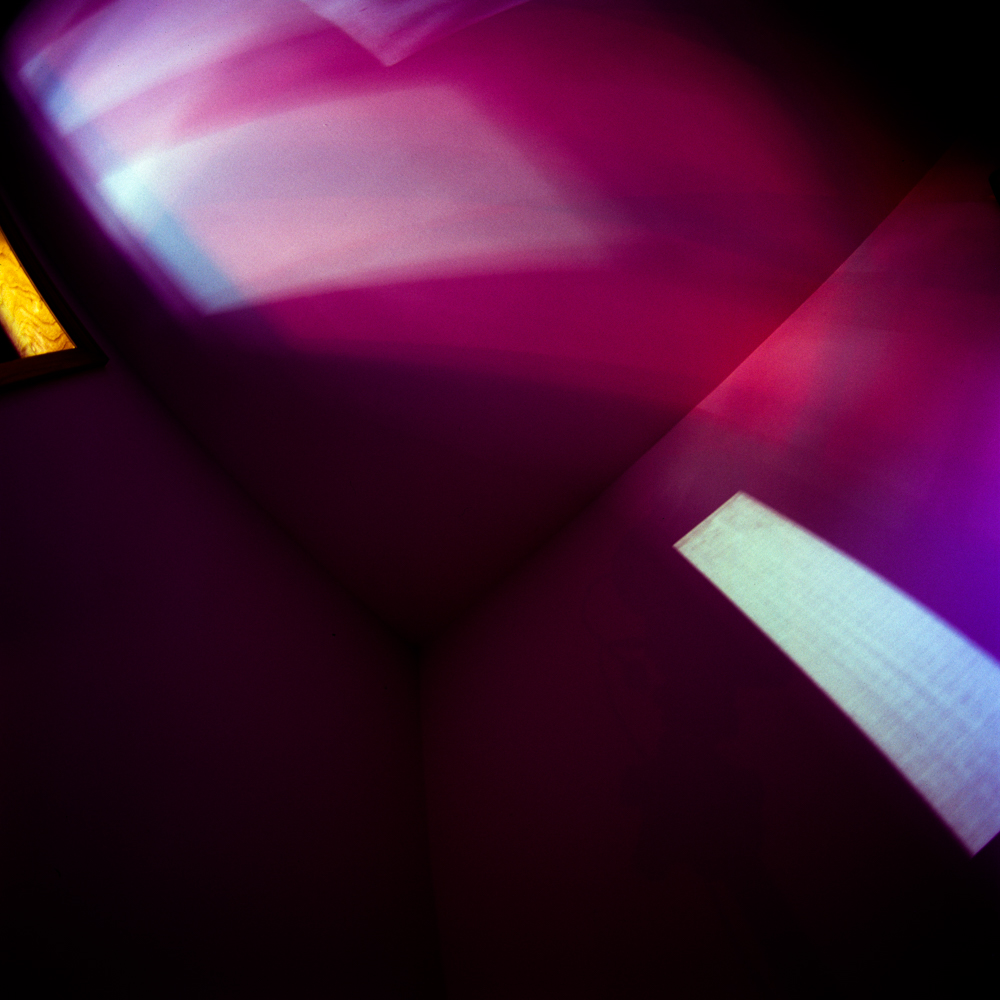

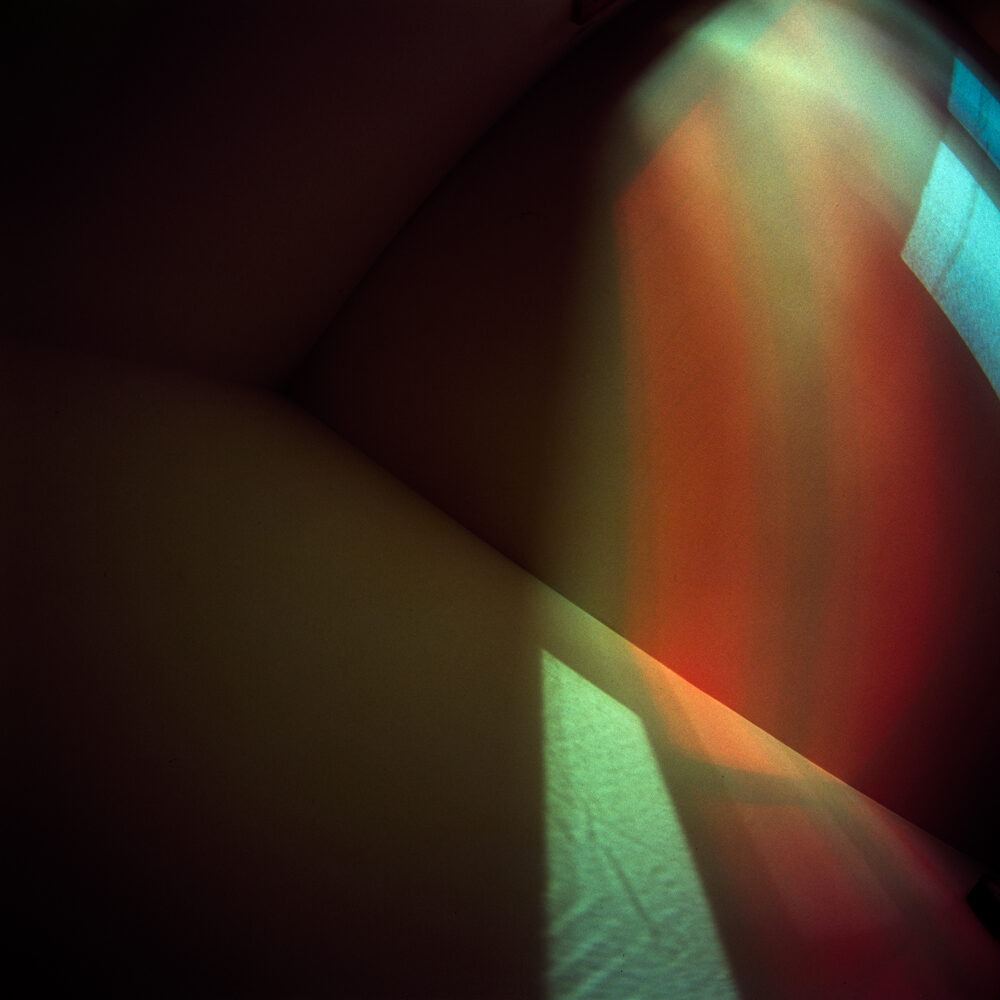

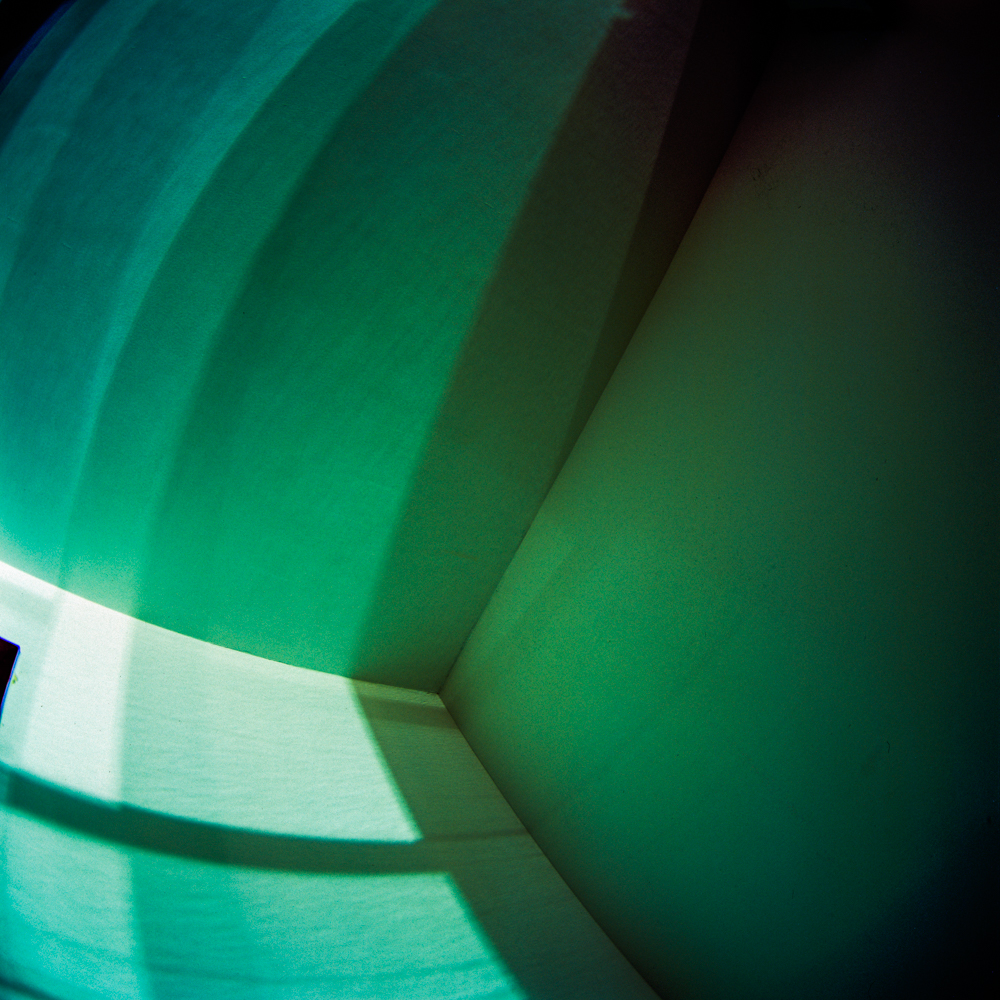

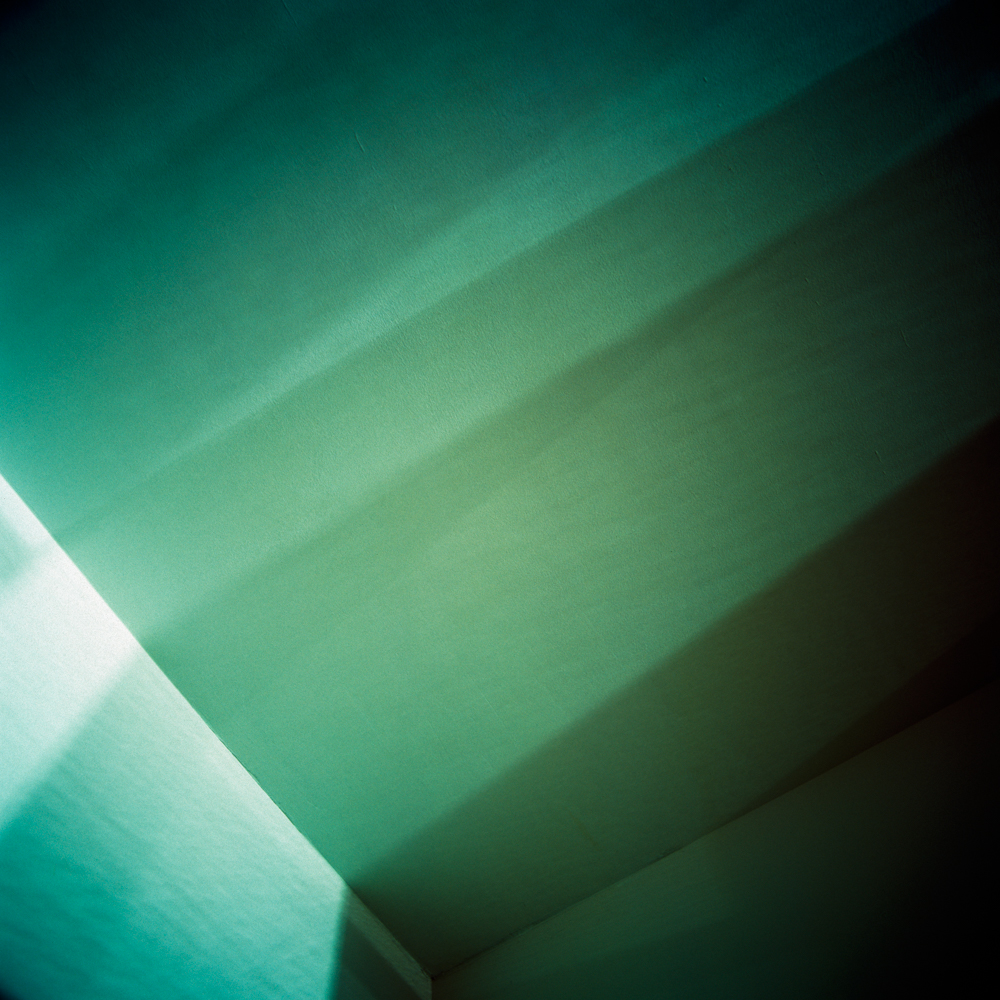

As a photographer, the camera was applied to expand my vision. It record what was going on when I was in deep sleep and the visual sensation was closed. The camera lens was set up to focus on the surroundings such as ceilings, walls, and corners of my room. The shutter of the camera would take pictures when I was not awake. When my perception was limited and cut off from the usual, the camera started to see, to reveal the world I never saw.

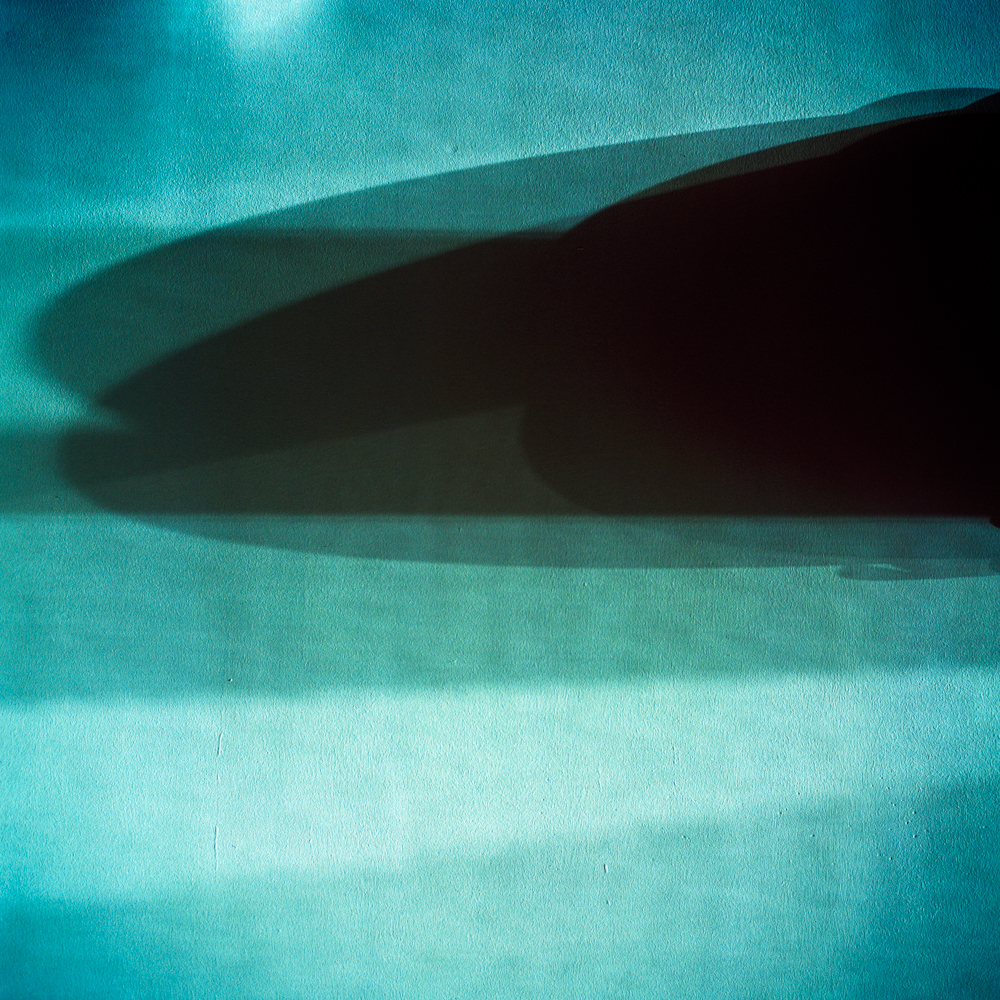

Every day and every night several kinds of light, came from the streetlamps, headlights, and so on, went through the windows and reflected around. Rays of light implied that something traveled through time and space. The light caught by my camera left a stroke, a layer on the film. In other words, something or someone passed by, but their traces entered my room and were recorded by my camera.

A Film by Wen-Han Chang

A Introduction by Amy Taubin

A Review By Lyle Rexer

Wen-Han Chang: Strange World at the Griffin Museum of Photography at the Greater Boston Stage Company By Lyle Rexer, March 5, 2019One thing we can say about contemporary photography is that, in contrast to the “objectivity” of 20 years ago, what you see is not necessarily what you get. It would be no more than a commonplace to point out that Taiwan-born photographer Wen-Han Chang’s diaphanous photographs testify to the broad acceptance of abstraction in photography. These kinds of photographs are literally everywhere. But there is no such thing as abstraction as trend or movement, only a wide variety of approaches, each to be engaged on its own terms.

On the surface, Chang’s color photographs capture shadows and reflections of colored light in a windowed room (or several rooms). They are lovely to look at, with their shifting planes of color, angles, and lens-based distortions. But even without knowing anything about them, there is something unsettling, even chaotic in them that threatens to break through their decorousness. Chang explains that he wanted to make a record of what was happening while he was asleep. He set up cameras to record what the light was doing around him, and by extension to him, in the space where he slept. It is a kind of theater he has recorded, nature caught unawares in the midst of a business (the prismatic play of light) that doesn’t care about his unconscious self. This reverses the Surrealist dictum of dreams as the royal road to creativity and knowledge. The oddness here is very real but hard to put into words. It’s a surveillance project in which there is no perpetrator, no intruder, yet a kind of breaking and entering is taking place. This sense of the unseen (by the sleeping subject) gives rise to feelings of vulnerability and a loss of control that absolutely contradict the authority usually conferred on the photographic viewer and of course on the photographer. Photographs usually show what the photographer saw, not what was completely missed.

It is fascinating that Chang worked for several years as a medical photographer, looking at subjects from the outside and, so to speak, attempting to get inside. It almost seems as if the entire basis of his art in this exhibition is simply to reverse that process, but with the same scientific impulse, to make visible what hides from us.

A Review by Natasha Chuk

Strange World (2018) is a short experimental film and photographic series by artist Wen-Han Chang that merges color, light, and ambient sound at a frenetic pace. The work is inspired by a series of photographic tests made to explore what happens when the artist is asleep: a record of time, events, and slumber, which culminates in a meditative arrangement of optical distortion, perspective, and visual perception.

Chang set up a camera in his bedroom—changing the position to show a corner, the ceiling, the wall—and recorded over the course of multiple evenings. The images depict movement outside of the window, capturing the traces of passing objects and people, whose shadows are cast on the surfaces of the bedroom to form a shadow puppet theater of nocturnal events. In the film, the recorded sound starts, stops, and overlaps in a highly textured aural mix: the combined sounds of a relentless snore, street traffic, sirens, and indistinct chatter collectively whir into a dreamy soundscape. The kinetic frenzy of this experience is delightful in its revelation of the interplay between the artist at rest and the activities that persist around him.

Uncanny is a useful term here to describe the combined feeling of strangeness and familiarity produced by the environment of Strange World, yet I find this adjective inadequate in describing this work. While it does create (or reveal) the strange world that surrounds one while asleep in a familiar environment, Strange World is more precisely a phenomenological study of sleep, surveillance, and the theater of activity resulting from the interaction between interiors and exteriors. Interior here refers to the bedroom and the dreamworld of the sleeper, and as such, exterior can be understood as the outside world of the dwelling and the external environment outside of the body. In fact, numerous binaries are collapsed here: inside/outside, mind/body, asleep/awake, personal/public, and so on. The effect channels a dreamlike state across the images and the film’s 16-minute duration.

The room becomes a zero-point of orientation, the point from which the world unfolds and comes together, distinguishing between here and there, and inside and outside. Things seen and unseen, perceived and unperceived, swell as the camera fixes its gaze in different directions. In this way, the camera produces a stage for the spatial sensations that surround the body in its unconscious presence. We are offered hints of the contours of this space, though our perspective remains fixed, oriented toward one corner, then another, of the habitual space. Chang’s camera orients us toward what’s implied outside of the frame. Our orientation is filtered through and translated by light but also partially produced by sound. We are situated somewhere between street traffic and human snoring. It’s hard not to imagine oneself as a specter who hovers invisibly above the sleeper, joining forces with the spirit world to keep watch and form a third-person consciousness.

We begin to get a sense of how our perception is shaped during moments when we are less aware of our enmeshment in the world. As our bodies rest, the world around us persists: Strange World produces evidence of the nightly ritual that takes place not behind but outside of closed eyes. It offers clues to the relations between the objective world and the perceived world, and as viewers, we sit at the threshold between the two. It calls to mind Merleau-Ponty’s ideas about perceptual consciousness and the ways in which the ties between the self and the world are elucidated. We recognize, and perhaps are asked to confront, the world’s intersubjectivity through the shared perspective between artist and camera. This experiment dissolves the separation between subject and object, illustrating the self and the way it’s entangled with the environment, circumscribing the real—perception—through the imagined.

Strange World offers an account of what appears beyond closed eyes as a kind of night watch to offset the unknown. Despite his physical orientation in space, the perceptual improbability of Chang’s awareness of external events during sleep can be articulated with the assistance of his camera. His previous experience as a medical photographer seems to inform his interest in the camera’s ability to at once resolve the unknown and generate new questions, a reading of perceptual presence and absence with presence understood as much through what is absent from the frame and from our perceptual register as what is evident. The limits of Chang’s camera’s discovery and the presentation of those results are a welcome, disorienting visualization of sleep, waking life, and wakefulness in which the recorded space becomes a perceptually muddled threshold between interior and exterior, time speeding by and stagnating. As we listen to the sleeper in the film, we can’t help but feel an entanglement between this theater of surveillance, the artist’s dream state, and our own consciousness. Though much remains perceptually unknown, our perceptual experience is nonetheless heightened in ways that feel both strange and familiar.

—

Natasha Chuk is a New York City-based, Latinx critical theorist and independent curator interested in media studies, film, experimental art, and creative technologies in a global context.

I love these pictures; beautiful, mysterious, otherworldly.

The world is mysterious, complicated, multi-dimensional, colorful, and beautiful, during our sleep, with or without good dreams or nightmares; best of all, it can be explored and recorded by a camera!